Research takes Dr. Emily Taylor to the British Library in London

Dr. Emily Taylor, professor of English and director of the women’s and gender studies program at Presbyterian College, spent her summer retracing the footsteps of Caribbean writers whose voices helped define anticolonial movements of the 20th century.

Her journey took her to the British Library in London, where she immersed herself in the archives of Jamaican novelist Andrew Salkey as part of an Eccles Institute Visiting Fellowship.

Taylor’s project examines how Casa de las Américas — the Cuban cultural institute founded in 1959 — became a hub for writers, translators, and intellectuals across the Caribbean and Latin America. She is writing a book that highlights how Casa’s translation projects, cultural congresses, and publishing efforts brought Anglophone Caribbean writers into conversation with their Spanish- and French-speaking neighbors during a pivotal era of independence and Cold War diplomacy.

A Lifelong Fascination with Caribbean Literature

Taylor describes her path into this field as somewhat unconventional.

“My main area of specialty is Caribbean literary studies, but my training was in comparative literature, so I’ve always worked across languages — Spanish, French, and English,” she said. “That led me to focus on translation as a way the Caribbean could come together in literary studies.”

Casa de las Américas quickly emerged as central to that story. Established just months after Fidel Castro came to power, the institute became not only a cultural showcase for Cuba but also one of the few publishing houses in the region willing to devote state resources to translating entire Caribbean novels into Spanish.

According to Taylor, this made it possible for readers in Havana to engage with voices from Barbados, Jamaica, and Guyana — neighbors just a short flight away but often linguistically isolated.

“It opened up these connections across the region,” she said.

Focus on Independence and Solidarity

Taylor’s research centers on the late 1960s and 1970s, when Casa began strategically reaching out to Anglophone writers at the same moment newly-independent Caribbean nations were developing their own national identities.

Her project highlights the 1968 Cultural Congress in Havana, when Cuba hosted 500 intellectuals from around the world — including many emerging figures in Anglophone Caribbean literature.

“Right at the moment these countries are winning independence, that’s when you see Casa reaching out to Anglophone writers,” Taylor explained. “It was part of Castro’s attempt at soft diplomacy and solidarity.”

Her Eccles Fellowship proposal outlined how she will anchor the book around ten Anglophone novels translated by Casa. Among them are George Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin (1953), Roger Mais’s The Hills Were Joyful Together (1953), and Jan Carew’s Black Midas (1958). Each reflects anti-colonial struggles in Barbados, Jamaica, and Guyana and found new audiences through Spanish translations published in the 1970s.

Archival Discoveries in London

At the British Library, Taylor spent three weeks immersed in the Andrew Salkey archive, which contains extensive correspondence, manuscripts, and personal papers. Access was slowed by lingering restrictions following a cyberattack that had crippled the library’s systems, limiting her to just four files per day.

That pace proved fortuitous.

“Some files were hundreds of pages of correspondence going back 30 years, others were much thinner,” Taylor said. “It was good I had three weeks because I needed to pace myself.”

Among her most exciting finds was an unpublished 170-page manuscript of poetry by Salkey. She painstakingly scanned each page on her phone to preserve it for further study. She also handled letters adorned with Casa’s distinctive modernist letterhead and exchanges between Salkey and writers across Canada, the Caribbean, and the United States.

“It was really neat to see how interconnected people were before the Internet,” she said. “They were still building global solidarity networks in the 1960s and 70s, despite racism, Cold War pressures, and scarce resources.”

The British Library Experience

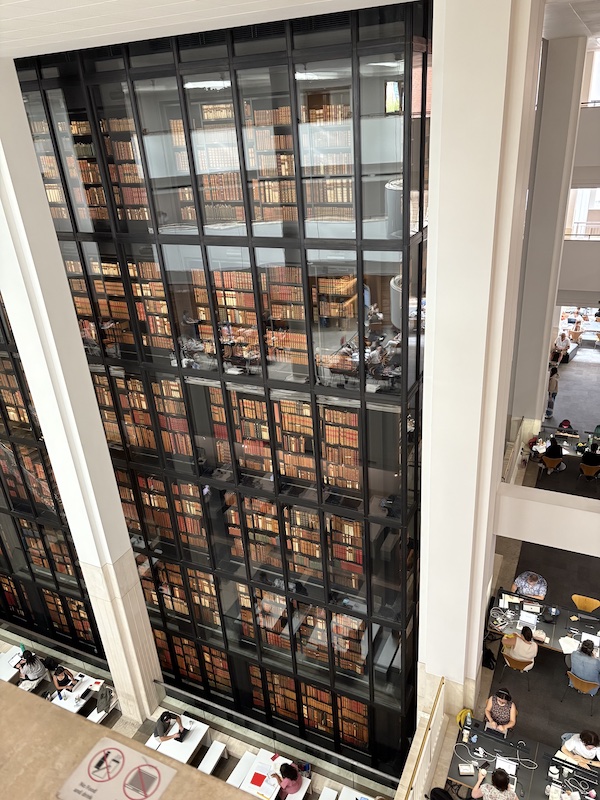

The British Library, Taylor said, provided not only access but also community.

“There were scholars from all over the world there. It felt like a ‘nerd home,’” she laughed. “You’re in this incredible building, designed like a ship, with King George III’s entire library displayed in glass in the center, and surrounded by artifacts like a copy of the Magna Carta.”

She capped her fellowship with a presentation for library staff and fellow researchers, sharing her findings from the Salkey archive.

On weekends, she took brief trips outside London — to Norwich on the east coast and to York, where she met her brother. But most of her days were spent in the reading rooms, balancing note-taking with the thrill of holding history in her hands.

Impact on Teaching at PC

Although her sabbatical was research-focused, Taylor says the experience will shape her classroom teaching.

In PC’s Introduction to Translation Studies, Postcolonialism, and World Literature courses, she draws on her scholarship to demonstrate how translation connects literary communities. She also uses her own research process to model persistence and creativity for undergraduates.

“It’s important to show students that even advanced researchers hit dead ends, revise questions, and make surprising discoveries,” she said. “Sharing that process can inspire students who are just beginning their own research journeys.”

Looking Ahead

Taylor is now drafting the early chapters of her book, tentatively titled Cuba and the Anglophone Caribbean Novel: Translation and Revolution at Casa de las Américas. She expects the project will not only contribute to Caribbean literary history but also engage broader audiences interested in how culture intersects with politics.

By highlighting translation as both a literary and political act, Taylor’s work sheds light on the solidarity networks that shaped Caribbean identity in the postcolonial era.

Her discoveries at the British Library — from Salkey’s unpublished poetry to Casa’s correspondence — are already helping her tell that story.

“Casa was a space where voices from across the Caribbean could meet, exchange ideas, and be heard in new languages,” Taylor said. “It reminds us how powerful literature can be in bringing communities together.”